Safari Retreats Case: Interpreting 'Plant and Machinery' and Scope of Input Tax Credit in GST Era

The Safari Retreats judgment clarified that Input Tax Credit (ITC) cannot be denied under Section 17(5)(d) when immovable property is constructed for further taxable supplies like leasing, preserving the integrity of the GST credit chain

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) was introduced in India with the promise of transforming the country’s shattered indirect tax into a unified, consumption-based taxation system. One of the key pillars of this framework is the Input Tax Credit (ITC) mechanism, which is a feature to ensure that tax paid at earlier stages of the supply chain is set off against the tax payable on output and thereby prevents the cascading of taxes.

The GST too met with its share of teething issues. One such contended feature was Section 17(5) of the Central Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017, which is an exception clause that carved out certain circumstances where ITC would not be available. Specifically, clauses (c) and (d) of this section disallowed ITC on goods and services used in the construction of the immovable property.

This case, Chief Commissioner of CGST & Ors. v. Safari Retreats Pvt. Ltd. & Ors., brought a pressing question: Should ITC be denied to a business that constructs a commercial mall, not for sale, but for renting it out, which is a supply on which GST is undeniably paid?

The dispute went all the way to the Supreme Court, resulting in a judgment that not only interpreted the law but sought to protect the broader principles upon which GST is based.

Input Tax Credit and Its Barriers under Section 17(5)(c) & (d)

Input Tax Credit (ITC) forms the bedrock of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime in India. ITC is designed to eliminate the cascading effect of taxes by allowing businesses to claim credit for the GST paid on inputs, whether it may be goods or services, that are used in the course or furtherance of their business. The intent is simple that the tax should be levied only on the value added at each stage of the supply chain, not on the entire transaction value.

Comprehensive Guide of Law and Procedure for Filing of Income Tax Appeals, Click Here

Section 16 of the CGST Act, 2017 lays down the eligibility for claiming ITC, which states that a registered person is entitled to claim credit on input goods and services used in the business, which are subject to certain conditions.

The provisions at the heart of the dispute were Section 17(5)(c) and (d). These clauses barred ITC in two specific cases, such as

- Clause (c) disallowed ITC on works contract services when supplied for the construction of an immovable property (other than plant and machinery), unless it was for further supply of works contract services.

- Clause (d) went further and disallowed ITC on goods or services received for construction of an immovable property (other than plant or machinery) on the person’s account, even if it was for business use.

These restrictions have been the subject of significant controversy. While they aim to prevent misuse of credit in cases where the end use is not taxable (such as personal use or sale of immovable property after completion certificate), their application has often led to denial of ITC even in cases where the constructed asset is used to generate taxable revenue, such as leasing of commercial buildings.

The revenue department read these clauses strictly, disallowing ITC for any construction activity leading to immovable property, irrespective of whether the constructed asset was used for further taxable supplies like leasing or renting.

But the petitioners in this case saw a contradiction. If GST was being charged on rental income from the very premises whose construction had attracted GST on inputs, wouldn’t denial of ITC amount to double taxation?

Also Read:Denial of ITC on Construction of Immovable Property: Supreme Court pronounces Judgment in Safari Retreats Case [Read Order]

Also Read:Denial of ITC on Construction of Immovable Property: Supreme Court pronounces Judgment in Safari Retreats Case [Read Order]

Facts of the Case

Safari Retreats Pvt. Ltd. is a company engaged in the real estate business. They undertook the construction of a shopping mall with the clear intention of letting out units to various tenants. This was no speculative construction project, and it was a business model based on earning rental income, which is a taxable supply under GST.

In the process of constructing the mall, Safari procured a large number of goods and services ranging from steel, cement, wiring, and escalators to building variety interior design services and even expert advice from foreign shopping mall planners. All of these inputs were independently taxed under GST.

Over time, the company accumulated more than ₹34 crores in Input Tax Credit, but when it sought to utilise this credit against the GST payable on rental income, the department advised otherwise.

The authorities cited Section 17(5)(d) and claimed that ITC was not permissible because the mall constituted an immovable property constructed “on own account”.

Comprehensive Guide of Law and Procedure for Filing of Income Tax Appeals, Click Here

Also Read:GST Council Acts on Safari Retreats Case: Retrospective Amendment Proposed for Drafting Error on S. 17(5) in GST Act

Also Read:GST Council Acts on Safari Retreats Case: Retrospective Amendment Proposed for Drafting Error on S. 17(5) in GST Act

Procedural History

Safari filed a writ petition before the Orissa High Court, challenging both the interpretation of Section 17(5)(d) and its constitutional validity. The High Court ruled in Safari’s favour, holding that the denial of ITC in such a situation would defeat the very objective of the GST regime.

The Revenue appealed, and the matter reached the Supreme Court of India, along with several other connected writ petitions raising similar issues.

Issues

Three key questions were placed for determination before the Supreme Court,

- Whether the definition of “plant and machinery” in the Explanation to Section 17 applied to the phrase “plant or machinery” in clause (d)?

- What is the correct interpretation of “plant” in the context of clause (d)?

- Whether clauses (c) and (d) of Section 17(5) and Section 16(4) are unconstitutional?

Each of these questions went to the root of how GST should be understood and applied in a real-world commercial setting.

Also Read:GST Dept. Files Review Petition on Safari Retreats SC Ruling following 55th GST Council decision to Amend 'Plant and Machinery' Provisions

Also Read:GST Dept. Files Review Petition on Safari Retreats SC Ruling following 55th GST Council decision to Amend 'Plant and Machinery' Provisions

Arguments Before the Court

Petitioner’s Arguments

The assesses, including Safari Retreats and other commercial property developers, argued that clauses (c) and (d) were unconstitutional and violated Articles 14 and 19(1)(g) of the Constitution.

They contended that these provisions treated unequal situations equally, putting those who build to lease on the same footing as those who build to sell. There is no break in the credit chain in rental businesses. GST is paid at every stage, that is, from inputs used in construction to rental income on output. So, denying credit amounts to cascading of taxes, which GST was meant to eliminate.

They argued that the phrase “on his account” must be interpreted to apply only when the building is used for personal or administrative purposes, not when it is used to supply taxable services like leasing.

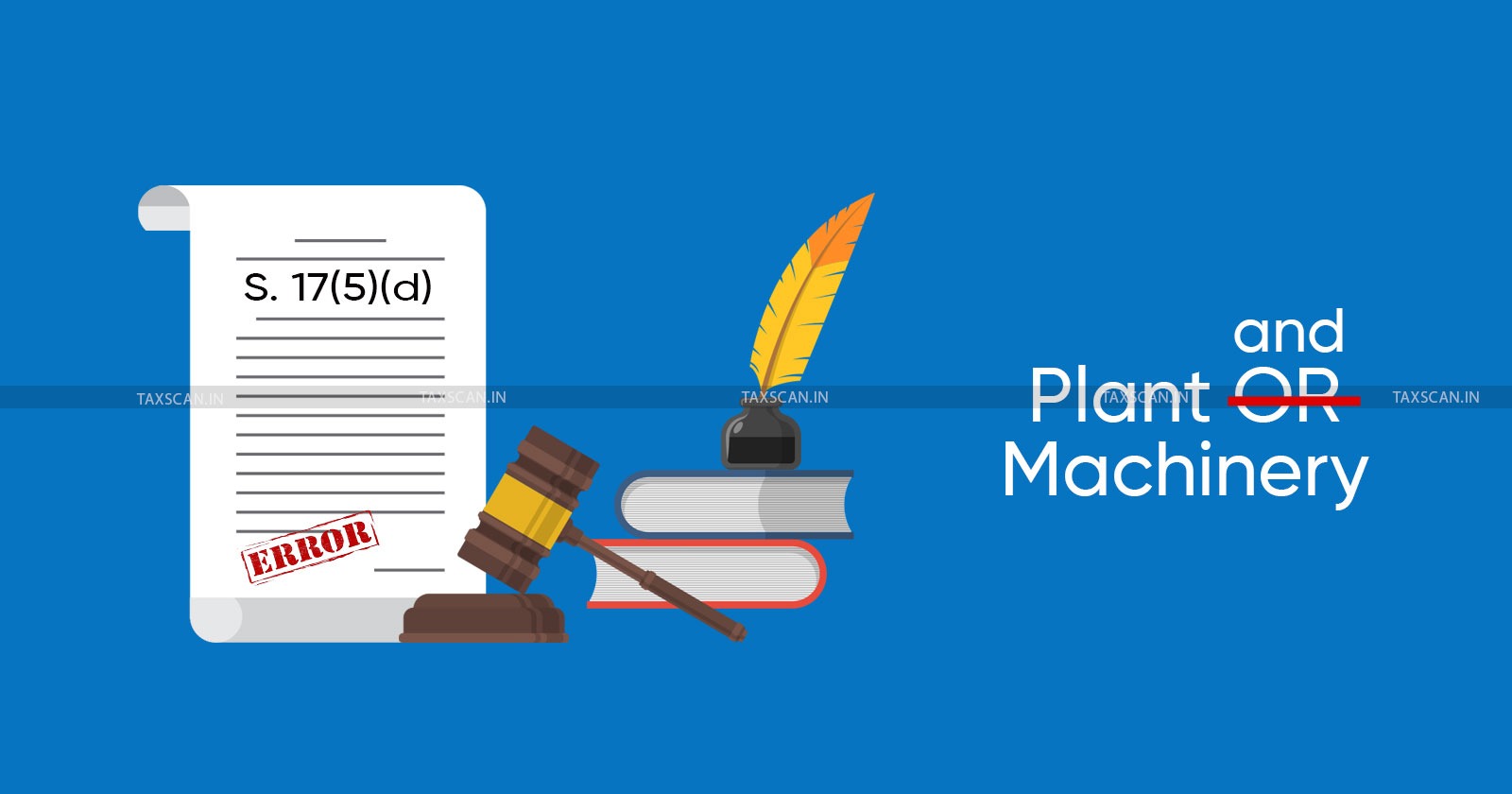

They also raised a semantic point that why does clause (d) use “plant or machinery” while clause (c) uses “plant and machinery”? This, they argued, was intentional and not accidental, and must lead to a different interpretation.

They argued that malls and hotels could themselves be considered “plant”, based on the functionality or essentiality test, i.e., if the building is the very tool of the trade, it may qualify as a plant.

Respondent’s Arguments (Revenue)

The Revenue, represented by the Additional Solicitor General, took a firm stand that Input Tax Credit is not a fundamental or constitutional right. It is a statutory concession, and Parliament is within its rights to limit it.

The classification made by clauses (c) and (d) is reasonable. They argued that construction of immovable property leads to a break in the tax chain, and therefore, ITC is rightly restricted.

On the language of “plant or machinery,” the ASG argued it was a legislative drafting error and should be read as “plant and machinery” for consistency.

If malls were allowed to claim ITC during the leasing period and then sell post-completion certificates without any GST, it would amount to unjust enrichment and revenue leakage.

Also Read:Legislative Drafting Error in GST Act: Impact of ‘or’ Instead of ‘and’ in Section 17(5)(d) and the SC’s Decision in Safari Retreats

Also Read:Legislative Drafting Error in GST Act: Impact of ‘or’ Instead of ‘and’ in Section 17(5)(d) and the SC’s Decision in Safari Retreats

Analysis

The Supreme Court took a delicate approach. The judges acknowledged the tension between strict interpretation of tax laws and real-world business logic.

The division bench comprising Justice Abhay S Oka and Justice Sanjay Karol noted that Section 17(5) is an exception to the general rule of credit under Section 16 and must be interpreted strictly. When ambiguity exists, that is especially when such ambiguity creates unjust results, the Court may adopt an interpretation that aligns with the overall scheme and object of the legislation.

The Court also found that reading “on own account” to include renting or leasing would lead to ridiculous consequences, such as breaking the credit chain despite tax being paid at both ends.

They also rejected the ASG’s argument that “plant or machinery” should be read as “plant and machinery”. The language, the Court held, was deliberate and cannot be altered by judicial intervention.

Decision

The Court upheld the constitutional validity of Section 17(5)(c) and (d), but clarified that “Clause (d) does not apply to the construction of an immovable property used for further supply of taxable services such as leasing or renting.”

Thus, Input Tax Credit shall be allowed in such cases, despite the text of clause (d), because the credit chain is not broken and GST is paid at every stage.

This judicial interpretation preserved both the textual sanctity of the law and the foundational principles of GST.

Also Read:[BREAKING] Supreme Court rejects Constitutional Validity of Blocking of GST Input Tax Credit in Safari Retreats Case, allows Revenue Appeal [Read Order]

Also Read:[BREAKING] Supreme Court rejects Constitutional Validity of Blocking of GST Input Tax Credit in Safari Retreats Case, allows Revenue Appeal [Read Order]

Comprehensive Guide of Law and Procedure for Filing of Income Tax Appeals, Click Here

GST Council’s Deliberations

While the judgment did not directly direct the GST Council, it effectively signals that certain anomalies in the law need attention.

The GST Council in its 55th meeting in Jaisalmer has proposed to retrospectively amend the GST law to restrict input tax credit on construction services. The amendment necessarily overturns the judgment of the Supreme Court.

The Council has recommended amending section 17(5)(d) of CGST Act, 2017, to replace the phrase “plant or machinery” with “plant and machinery”, retrospectively. Speaking with the media after the Council meeting, CBIC chairman said that the expression “plant or machinery” used in the said section of the GST Act was a drafting error, and that the proposed amendment seeks to correct the error.

Future Impact and Extension

By interpreting the phrase “on his own account” in a business-use context and clarifying that credit cannot be denied when the constructed immovable property is used for further taxable supplies, the Court has recalibrated the balance between legislative intent and economic reality.

At its core, GST is meant to be a destination-based, value-added tax. The Safari Retreats ruling reaffirms that ITC must flow seamlessly across the supply chain, and arbitrary restrictions, particularly where no break in the tax chain exists. It affirms the proposition that tax neutrality is sacrosanct, and credit blockage should be narrowly construed.

This interpretation now sets the tone for judicial consistency and is likely to influence decisions in a wide array of similar disputes, whether involving hotels, warehouses, industrial parks, co-working spaces, or any infrastructure that involves construction followed by leasing or renting.

The judgment also casts a spotlight on the legislative drafting inconsistency within Section 17(5) that is particularly the inconsistent use of the phrases “plant and machinery” and “plant or machinery.” The Court chose not to judicially rewrite this language but did signal that the difference in wording was deliberate, not accidental.

This judgment is likely to encourage developers and leasing companies to structure their tax strategies with renewed clarity, leading to revised assessments and refunds where ITC was incorrectly denied in the past.

For example, entities operating malls, multiplexes, co-living spaces, industrial parks, and even educational campuses may now seek credit where the output supply remains taxable.

Finally, this judgment provides a framework for how courts should interpret economic legislation under GST. The Court preserved the text of the law while infusing it with commercial logic and constitutional principles, making it a guiding precedent for future tax disputes.

By refusing to strike down Section 17(5)(d) but instead interpreting it purposefully, the Court demonstrated how reading down a provision can protect both taxpayer rights and legislative intent.

In Lulu International Shopping Malls Pvt. Ltd. v. State Tax Officer (2024), the Kerala High Court set aside the denial of ITC on works contract services for mall construction, noting that the assessing officer failed to consider the Supreme Court’s ruling in Safari Retreats. The Court directed a fresh examination, holding that whether such buildings qualify as "plant or machinery" is a factual question linked to the nature of the business and must be assessed accordingly.

In Mother Earth Environ Tech Pvt. Ltd. (2024), the applicant sought an advance ruling on whether a landfill constructed for waste treatment could qualify as "plant or machinery" and thus be eligible for ITC .

Comprehensive Guide of Law and Procedure for Filing of Income Tax Appeals, Click Here

The Authority for Advance Ruling (AAR) referred to the Supreme Court’s judgment in Safari Retreats, noting that the phrase “plant or machinery” in Section 17(5)(d) must be interpreted based on functionality, not just structural form. Although the landfill was ultimately held to be a civil structure excluded from ITC, the ruling affirmed the relevance of Safari Retreats’ functional-use test in determining ITC eligibility.

In response to Safari Retreats, the Finance Bill, 2025, introduced a retrospective amendment to Section 17(5)(d) of the CGST Act. The amendment replaced the phrase “plant or machinery” with “plant and machinery”, aligning it with the defined term used in clause (c).

This change, made retrospectively effective from July 1, 2017, effectively nullifies the interpretive distinction recognized in Safari Retreats, and closes the door on ITC claims based on the broader reading of "plant or machinery". The amendment underscores the legislature’s intent to maintain a strict barrier against ITC on civil construction, even when used for taxable output services.

Also Read:Finance Bill 2025 Amendment to S. 17 (5)(d) Reversed Ruling of Supreme Court in Safari Judgement

Also Read:Finance Bill 2025 Amendment to S. 17 (5)(d) Reversed Ruling of Supreme Court in Safari Judgement

Conclusion

The Safari Retreats case is more than just a technical dispute about tax credits. It is a landmark interpretation of how economic realities and legislative intent must harmoniously coexist in a complex tax system like GST.

By reading the law in light of the scheme and purpose, the Supreme Court ensured that businesses are not penalised for participating in taxable supply chains as long as there is no break in the tax trail.

In doing so, the Court reaffirmed a basic principle: GST is meant to tax consumption, not investment, and certainly not in a manner that disincentivises compliance.

This decision will likely serve as a guiding precedent for all future disputes involving input tax credit and will continue to shape India’s evolving indirect tax landscape.

Support our journalism by subscribing to Taxscan premium. Follow us on Telegram for quick updates